Most ski villages—that space at the base as you approach the lifts—can be divided into three starkly different subgroups: places that look like a municipal building with swanky pretensions, places that look like they were a sleepy town before skiing boomed, and places that look like they were dropped in whole by crane over a two-week period sometime in 1974.

Bridger Bowl belongs in the first group; Park City and Winter Park belong in the second; Vail and Tahoe’s Northstar in the third. The first group looks utilitarian because it is: it’s either municipal or a standalone, shoestring mom-and-pop operation. Villages in the middle group have evolved into a weird mix of shabby-twee bars and shops. The last have arrived in a sudden burst of near-Biblical creation, like Centennial, Florida or a million exurban developments two highways past the ring road in your city. Like Frontierland or any of the other fiefdoms in the Magic Kingdom. And that is why we say these places are Disney-fied.

It turns out, though, that all ski hills have a touch of Walt Disney about them. If you started skiing before 1968, this might not be news, but for the rest of us it is a revelation that the green-blue-black taxonomy of ski runs came from a team at Disney. Insidethemagic.net (which seems to be a Disney fan site) has detailed this nicely in Walt Disney’s Everlasting Effect on North American Ski Resorts.

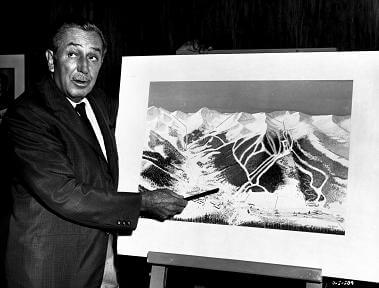

In the early 1960s, toward the end of his life, Walt was exploring the idea of building what was to be called Disney’s Mineral King Ski Resort in a valley that would eventually (in 1978) be incorporated into Sequoia National Park. It might be worth a moment of your time to consider what an actual Disney-fied ski resort would look like, and whether it would be much different from the village at, say, Whistler. It might have felt weirdly inauthentic, but the Disney capacity for making “fun” accessible and compelling might have accelerated and sustained skiing’s appeal to the masses. An account posted to the Disney Family Museum describes it as a $35 million project that would have drawn 2.5 million visitors annually. Interestingly, the proposed ski area would have banned automobiles from the valley, with a large remote car park and a “high-capacity public conveyance” taking you to your lodging. That could have been a bus, of course, but you know Walt was thinking about a monorail. Eventually, a cog railway was proposed.

Before the project was ultimately shelved (due to opposition by environmentalists) a team at Disney had designed an easy-to-understand scheme for trail signage—later adopted by the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA) and now ubiquitous across North American ski resorts. Green circles, blue squares, black diamonds.

Prior to the Disney system, ski areas had individual systems. The NSAA recognized the problem and released its initial attempt at a harmonized system in 1964: “A green square labeled the easiest runs, a yellow triangle for ‘more difficult,’ a blue circle for ‘most difficult,’ and a red diamond for ‘extreme caution.’” A few years later—in 1968—the NSAA heard about the Disney scheme, found it to be superior, and adopted it. We’ve had a few tweaks since, including the adoption of blue square-black diamond signs to indicate something tougher than that sweet groomed blue where you can basically let your skis run while you sway to whatever is coming through your headphones. (Be careful about that, of course; you need to hear those people around you.) The orange oval signifying a terrain park is also something not of the mid-60s.

A tip of the hat to the Disney folks for such a simple and easy-to-grasp system. It seems obvious to us, but for some reason ski resorts in Europe and Japan differentiate their runs using only color: blue-red-black circles in Europe, green-red-black circles in Japan. Using only color means a colorblind person will almost certainly have a few terrifying moments on the wrong run. These inevitably happen whenever you explore a new resort; it seems cruel and dangerous to create these situations unnecessarily.

Photo: The Walt Disney Family Museum